Fiocruz study assesses the evolution of Brazilian leishmania

08/03/2021

Maíra Menezes (IOC/Fiocruz)

When the first Portuguese and Spanish ships moored along the coast of the Americas, microorganisms that caused common disease in Europe, but which had never occurred in American soil, disembarked along with the crews. The causer of visceral leishmaniasis, Leishmania infantum is part of a group of microscopic travelers which, despite the huge differences between the Old and the New World, managed to settle here quite well.

More than 500 years later, a study suggests that the evolution of this pathogen in the tropics has followed a surprising trajectory. Leishmaniasis that suffered a DNA deletion, that is, lost part of their genetic code, have spread over most of Brazil. The phenomenon has never been observed in Europe but has also been recorded in Honduras. This deletion had been observed in some Brazilian strains and may be related to resistance to miltefosine, a drug used to treat visceral leishmaniasis in India and which has shown reduced efficacy in a clinical trial in Brazil.

Mapping shows that L. infantum parasites with deletion in the genome (in white) are widespread from North to South of Brazil (credit: Schwabl, P., Boité, M.C., Bussotti, G. et al)

Based on the highest number of L. infantum genetic sequencing ever done in Brazil, this new study shows, for the first time, the reach of the genetic trace in Brazil. Seventeen Brazilian states were studied and 15 of them showed mainly microorganisms with a deletion.

“We have found the deletion in all of the country’s regions. Our findings show that the occurrence of the deletion is frequent and geographically dispersed, which may be a reflection of the evolutionary process of adaptation, which has favored the dispersion of the parasite here”, states Mariana Boité, researcher of the Leishmaniasis Research Laboratory of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC/Fiocruz) and who shares the first authorship of the study with Philipp Schwabl, of the University of Glasgow.

The correlation between the genetic trait and the failed treatment with miltefosine was found in a previous study, which analyzed the genome of 26 strains of L. infantum referring to patients that participated in the clinical trial in Brazil.

“As this is about a limited number of cases, it is possible that a bias has taken place. But considering that most of the Brazilian strains have this deletion, it is crucial to make tests to investigate whether there is a relation between this genetic trait and susceptibility to miltefosine and other drugs. If this resistance is confirmed, it would jeopardize the use of the drug in Brazil, for patients as well as for dogs”, states Elisa Cupolillo, head of the Leishmaniasis Research Laboratory and coordinator of the study. She also mentioned that the drug is not yet used in human cases in Brazil, but it has already been authorized to treat canine visceral leishmaniasis.

The result of strong international cooperation, the study was led by IOC/Fiocruz in a partnership with the University of Glasgow, in Scotland, and the Pasteur Institute, in France. Other participants in the study were the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), the Karolinska Institute, in Sweden, and Charles University, in the Czech Republic. The findings were published in Communications Biology, of the Nature-Springer Research group.

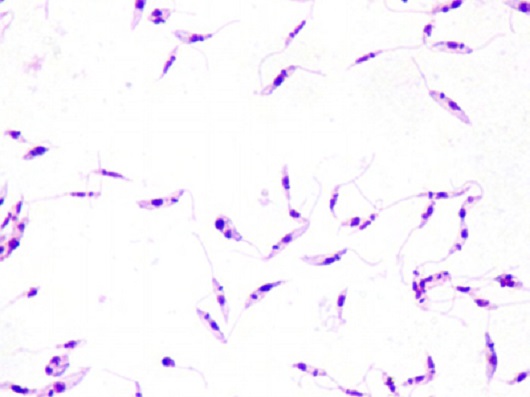

The research included genetic sequencing of 59 parasites deposited in the Leishmania Collection of the IOC (image: Leishmania Collection / IOC / Fiocruz)

“The scientific collaboration established by the IOC with the University of Glasgow and the Pasteur Institute is at the foundation of this study. The combination of different expertise was crucial for carrying out a large number of genetic sequencings and robust bioinformatics analysis, which have resulted in unheard-of results on the genetic diversity of L. infantum parasites in Brazil”, says Cupolillo.

“This study has managed to bring light on the distribution and evolution of a genetic deletion in L. infantum, which can have significant consequences for our ability to treat the disease”, highlights Martin Llewellyn, researcher of the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine.

“Our non-stop collaboration hopes to understand how this deletion offers a selective advantage to parasites and how we can explore this piece of information to improve control measures against visceral leishmaniasis”, states the head of the Unit of Molecular Parasitology and director of the Department of Parasites and Vector Insects of the Pasteur Institute, Gerald Spaeth.

In addition to the Leishmaniasis Research Laboratory, the study also boasts the participation of the Laboratories of Molecular Biology and Endemic Diseases and Molecular Biology of Parasites and Vectors of the IOC. The strains sequenced in the research were obtained from the institute’s Leishmania Collection, which has almost four thousand strains of Leishmania of different species, collected mainly in Brazil.

Losses and gains

The part deleted from the genome of the Brazilian microorganisms is located in chromosome 31 and is responsible for orienting the production of four molecules. Among these is an enzyme that is important for the nutrition of the pathogen, and it is also considered a virulence factor, contributing to infection as it helps L. infantum escape from the host’s defense mechanisms. The fact that microorganisms can easily survive with and even benefit from the absence of this gene drew the attention of researchers.

“As for the three other deleted genes, there are different copies of them in the DNA, and the parasite may not be very hampered by it. But the gene that orients the production of the 3’ ectonucleotides enzyme has only one other copy described in the genome of Leishmaniasis, and it is a very important enzyme in the parasite’s biology”, explains Boité.

In laboratory trials, researchers have also confirmed the very low activity of the 3’ ectonucleotides enzyme in strains with the deletion and discovered a possible compensatory mechanism for its function. Tests have shown that these microorganisms have higher activation of another enzyme, called ecto-ATPase, which acts in a parallel mechanism that is also very important for the parasite.

While the biological role of the 3’ ectonucleotides enzyme needs to be compensated for, the reduced virulence of the pathogen can be an advantage from the evolutionary point of view. “We still need to investigate all the consequences of this deletion. For instance, if the parasite does not cause a severe infection, the dog, the main reservoir of visceral leishmaniasis, can remain asymptomatic. This is good for the parasite, as a sick animal tends to remain retracted, while asymptomatic individuals circulate in vegetated areas and in households, disseminating the parasite”, Cupolillo mentions.

Genetic diversity

To get to the results, researchers have sequenced the complete genome of 59 samples of L. infantum from Brazil, the highest number decodified in the country. Seventy-five other samples were submitted to PCR, which punctually detects the presence or the absence of the deletion. By gathering information deposited in genetic databases online, scientists arrived at a total of 201 samples analyzed, of which 177 came from Brazil.

The deletion was found in 126 Brazilian parasites and in two from Honduras. In phylogenetic analysis that investigates “kinship” relations between parasites based on their genetic similarities, researchers have identified that the deletion is a trace inherited from a distant ancestral. “Our analysis shows that this genetic trait came from the population that was imported from Europe. The issue that remains is the question of why this characteristic did not spread there but was selected here”, ponders Boité.

Taking into account the 17 Brazilian states with contemplated samples, researchers observed particular situations. Microorganisms with the deletion were not predominant in only two of the states. Mato Grosso do Sul was the only state that did not show parasites with the genetic trace in question. In the state of Piauí, most of the strains had no deletion. In Piauí as well as in Mato Grosso, three varieties of microorganisms were found: with the deletion, without the deletion, and heterozygotes, that is, parasites generated through the recombination of different strains, presenting a pair of the chromosome with deletion and another pair without deletion in their genetic code.

Among the different factors that can influence the genetic diversity of parasites, researchers have mentioned the variety of vectors present in different regions. In Europe, L. infantum infects insects of the Phlebotomus genus. In the Americas, the parasite is transmitted by insects of the Lutzomyia genus. Even within Brazil itself, there are different species of vectors. The main species is Lutzomyia longipalpis, but in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, for instance, the transmission cycle also happens with the participation of Lutzomyia cruzi”, says Boité.

Scientists highlight that the study raises many questions, and some of them should begin to be investigated in the next stage of the work. “In addition to the possible association with resistance, we would like to analyze exactly what are the consequences of the deletion on the parasite. How do these strains infect animals and vectors? What is the course of the infection? Are there differences between infections caused by parasites with and without the deletion? These are only some of the issues that can be significant for control actions against the disease and to which we need to respond”, highlights Cupolillo.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Brazil is one of the country’s most seriously affected by visceral leishmaniasis in the world, with more than 2.5 thousand cases recorded in 2019, according to the Ministry of Health. The disease is classified as neglected by the World Health Organization (WHO), hitting mainly poor populations in precarious living conditions.

In the urban environment, dogs are the main reservoir for these parasites. The vectors of the parasite are phlebotomine insects, popularly known as sandflies. They proliferate in damp places, with shade and organic matter, such as fruit and leaves, in addition to animal feces. These vectors contract the parasite when they bite infected animals, and then transmit it to humans through their bite.

The infection attacks internal organs such as the liver and spleen, and victims die in 95% of the cases in which early treatment is not administered. In Brazil, the treatment against leishmaniasis is offered free of charge by the Public Health System (SUS) and includes antimony drugs administered intravenously.